Irish Seisiún Newsletter

This Week’s Session 1

Tom,

Click on any image below to enlarge.

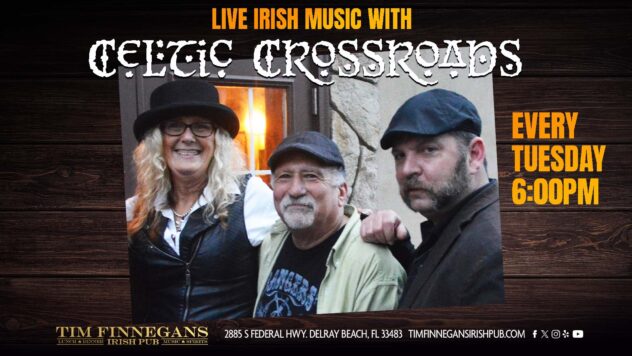

Find out what’s happening at Tim Finnegan’s this month.

.

Click here to view calendar

Finnegan’s supports us…Let’s support them!

.

“That’s How I Spell Ireland”

“That’s How I Spell Ireland”

Saturdays at 7 to 8 PM EST.

You can listen on 88.7FM or WRHU.org.

For a request please text me on 917 699-4768.Kevin and Joan Westley

Note: Show will be preempted whenever the NY Islanders have a Saturday game

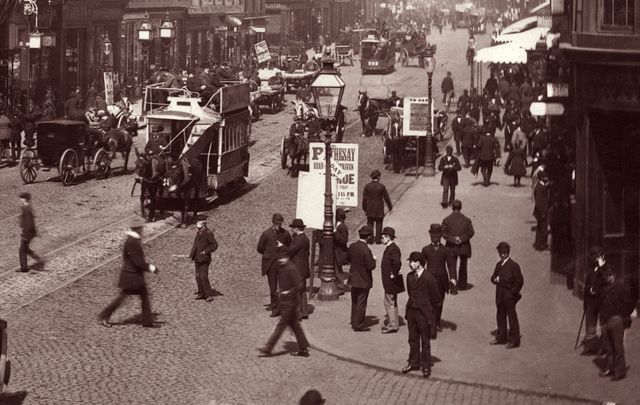

Old Ireland

Harvesting seaweed

Early 1900s

Recent Mail

Travel in Ireland

FAVOURITE PLACES IN IRELAND

Bunratty Castle, County Clare. (See it on a map here.)

Bunratty Castle is probably the most complete and best-preserved castle in Ireland. They even offer a unique dining experience – a world-famous medieval banquet! Check out this video of a medieval banquet in the castle to whet your appetite, and based on the

Irish Language

Tír gan Teanga, Tír gan Anam:

A land without a language is a land without a soul.

Submitted by our own

Anita

Seachtain na Gaeilge (English: Irish language week), known for sponsorship purposes as Seachtain na Gaeilge le Energia, is an annual international festival promoting the Irish language and culture, both in Ireland and all around the world.[1]

Established in 1902, it is the biggest Irish language festival in the world, reaching over 1 million people on 5 continents each year.[2

Energia has been a sponsor of the festival since 2017.[9] “Úsáid do Theanga” (English: “Use your language”) was the motto of the festival in 2020

The celebration takes place every March from March 1st to St Patricks Day.

Watch this short video “as gaeilge” to get the idea!

Seachtain (shach-tin) week

La (law) day

Mi (mee) month

Coicis (cuh-keesh) fortnight/2 weeks

Bliain (blee-an) year

Ta seachtain na gaeilge ar siul faoi lathair (taw shach-tin nah gaeilge air shool fwee law-hir)

Irish week is happening now

SIn e don seachtain! Slan agus beannacht.

Anita

Free Irish Classes

The classes are over zoom and are held at 12:00 eastern time the 1 st Sunday of every month.

It is basic conversational Irish and open to learners of all ages, especially beginners.

All are invited.

Hope to see you there!

slan go foill. Le dea ghui,

Anita

click here to register

Travel Quiz

Can you identify this site

and its location in Ireland

Send your guess to Tommy Mac at [email protected]

Answer in Next Week’s Newsletter

Last week’s answer

Redwood Castle in County Tipperary

This week’s Irish recipe

Traditional Irish hot cross buns

These spiced and fruity sweet treats, traditionally eaten during Lent, are said to have mythical properties

Zach Gallagher

Feb 18, 2026

Hot cross buns: The treat that ensures friendship marked with a sacred holy cross, they’re also delicious! Zach Gallagher

These spiced and fruity sweet treats, traditionally eaten during Lent, are said to have mythical properties

Hot cross buns are traditionally baked to be eaten during Lent, the 40 days before Easter. The bun acquired mythical properties over the centuries, and early literature reveals that the hot cross bun was also known as the Good Friday Bun.

The most famous story says the hot cross bun originated in the 12th century, when an English monk is said to have placed the sign of the cross on the buns to honor Good Friday. Throughout history, the bun has been credited with special virtues, among them ensuring friendship between two people sharing a bun. An old rhyme states, “Half for you and half for me, between us two, good luck shall be.”

Another tradition holds that a hot cross bun should be hung from the kitchen ceiling from one year to the next to ward off evil spirits. Healing properties were also attributed to it. Gratings from a preserved bun were mixed with water to provide a cure for the common cold.

There are loads of delicious ways to eat this legendary treat: you can slice them, toast them, and butter them. I love them toasted with real butter and strawberry jam.

Irish hot cross buns recipe

This recipe is an old family one, and it makes about 10 buns – but we always double it up.

Ingredients:

- 4 cups bread (strong) flour

- Pinch of salt

- 2 tsp mixed spice

- 6 tbs butter

- 2 tsp (1 packet) active dry yeast

- 1/4 cup caster sugar

- 1 egg

- 1 cup warm milk (30 seconds in the microwave will do)

- 1 cup dried seedless raisins

- Grated rind of an orange

Method:

Put the flour, salt, and mixed spice in a bowl, and give them a quick whisk to mix. Rub the butter into the flour mix until it resembles fine breadcrumbs. Add the yeast, sugar, beaten egg, and milk, and stir until a soft dough forms.

Knead for 10 minutes until the dough is smooth and elastic. If you are using a mixer to make these buns, let it run on low for five minutes with the dough hook. Add the dried fruit and grated orange rind, then knead for another minute.

Roll out the dough slightly and cut it into 10 pieces. Roll these into balls on the table using the flat of your hand and place them on a baking sheet or tray. Leave the same width between each bun so they have room to rise.

To make the cross, mix 1 cup of flour with about 3 tablespoons of cold water to make a basic soft dough. Roll it out really thin, then cut into thin strips. Dampen with a little water and stick to the top of each bun. Take a length of plastic wrap and brush it with a little cooking oil. Place this loosely on top of the buns (oiled side down) and leave in the kitchen to double in size – about 20 minutes depending on the weather and the warmth of the room.

Bake in a preheated oven at 390°F (360°F in a fan oven) for 20 minutes.

Hot cross buns were traditionally brushed with a sugar and water glaze when they’re still hot, but I prefer to brush them with local honey

Enjoy!

Sign up to IrishCentral’s newsletter to stay up-to-date with everything Irish!

For more from Zack see www.IrishFoodGuide.ie.

Poem of the Week

Nancy Lichtenberg’s poem about leaving Ireland

Irish woman’s poem of emigration will stir your heart

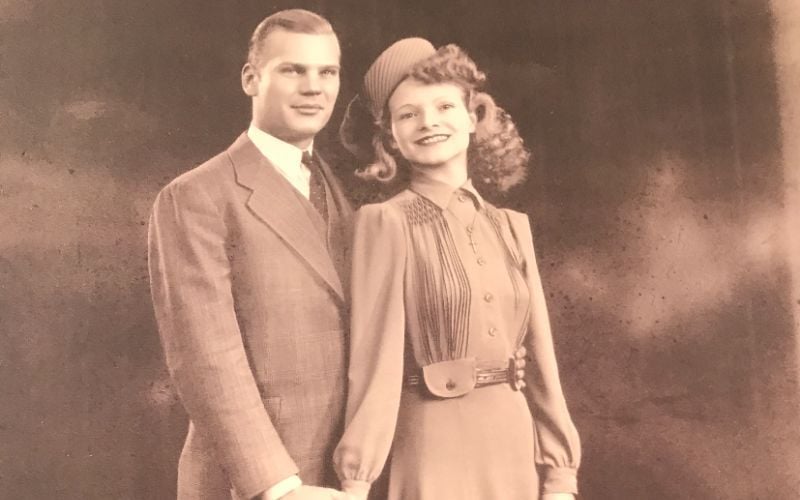

Irish woman Annie Carroll, who became Nancy Lichtenberg, penned this emotional poem about leaving Co Mayo and settling in the US some 50 years after emigrating.

Nancy Power shared on social media this emotional poem that her late grandmother Nancy Lichtenberg, aka Annie Carroll, penned about her experience coming to the US from Ireland.

Carroll was only 17 years old when she left her native Co Mayo, an experience she detailed in this unnamed poem she wrote in the 1980s.

“She was an amazing woman and had a great life until she died at the age of 86,” Power said while sharing her grandmother’s poem, “but she always held some sorrow as to being separated from her family and Ireland in the way she had.”

While Power’s mother believes Annie came from Cairn, a few miles from Charlestown in Co Mayo, Power was never able to locate a town with that name. She does know, however, that the family’s property was on the way to Knock, and the home place became part of Knock airport.

Power says her grandmother was sent to the US at the age of 17 in 1929. After arriving in New York, Annie went straight to Philadelphia.

Power explained that when her grandmother came to the US, people started calling her Nancy, saying it was the nickname for Ann, so Anne Carroll (Annie) became Nancy Carroll, and then upon marriage, Nancy Lichtenberg.

Power’s grandmother later moved to Atlantic City, New Jersey, and then back to New York, where she would live for the rest of her life, moving from the Bronx to Brooklyn, to Queens, and finally to Long Island.

“She married my grandfather on December 9, 1939, and remained married to him until her death on June 24, 1998,” Power said. “She had four children and eight grandchildren who adored her.”

Power added: “She only managed to visit Ireland once, 47 years after she left.

“Her parents and her youngest sister had passed away while she was gone.”

Power says her Nana would have been “delighted” to have her poem published.

Shared here, with kind permission of Nancy Power, is Nancy Lichtenberg’s poem about leaving Ireland:

Why did I have to leave home this way?

That question has been bothering me till this very day

I was so happy there as happy as can be

Because everyone I loved was all around me.

I guess there were no jobs for me in sight

And I wasn’t the only one who suffered such a plight

As you grow up you come to understand

The only place to find work is in some foreign land.

So naturally, it came my time you see–

And the night before I left home

They gave a farewell party for me

It eases the grief for both my family and me

My relatives and friends came from far and wide

I really don’t know how they all fit inside

The band was playing over by the wall

They were singing and dancing and having a ball…

But you know this happiness will soon end

And now my ordeal starts– saying goodbye to your friends

You know these people all your life through

To each one you say goodbye, it takes a part of you.

And people are leaving all night long

The first thing you know-It’s the breaking of dawn

But the worst part was still ahead of me

I had two sisters and brothers younger than me.

I could not stand the sad look on their faces

So I turned away to look for my suitcases

My mother said “Annie, the car is waiting outside”

At any other time, it would be a joy and a fun ride.

But this was a car hired to take me to Charlestown

That was where the train arrived in our town.

I can still see that train as it came around the bend

And the expression on Mother’s face seemed to say

………….I’ll never see her again…………..

And she held me so tight, tears fell like rain

Dad said “Bea, she’s got to get on the train.”

It was a difficult period with so much emotion and strain.

I stood on that train as it started to go.

And as usual, the train started up slow

I had time to wave more goodbyes

Though it was hard with tears blinding my eyes.

All of a sudden they disappeared from my view

Down inside my heart was breaking in two

I sat on the train and threw my head back

The rhythm of the wheels as they hit the track

Say–Let’s face it Annie, there is no turning back……

As I was traveling, this girl came up to say

I am leaving home for the USA

I am feeling bad and so blue

Do you mind if I sit here with you?

I said I don’t mind, please stay

Because I am going the exact same way

We said very little as we travelled on the train

Deep inside we were emotionally drained

We finally landed in Queenstown

I went to my room just to settle down

All of a sudden there was a knock on my door

It was the girl I met on the train just before

She said I can’t be alone this night through—

Would you mind if I stayed here with you

It was a large room with an extra bed

I’d be happy to have you with me I said

And after awhile, she said let’s get some tea

And that is when I remembered the whiskey Dad gave me

He said, I traveled by boat a lot–People get very sea sick

So before you go aboard tomorrow just take a little sip

I asked her if she would try the whiskey

She said that is alright with me

So I opened it up–it was the worst stuff I ever tasted

I asked her if she wanted more-She said “yes, it would be a shame to waste it”

So we sipped that stuff constantly

After awhile we got as silly as can be

We weren’t even speaking coherently

Regardless of what she said-it made no sense to me

So we cried and laughed all through the night

And all of a sudden, it’s broad daylight

The first thing I saw as I gazed towards the sea

Was this huge ocean liner–just waiting for me

I remembered that day as I got aboard deck

Two nights without sleep, I was a physical wreck

My legs were so tired I could barely stand

So I leaned on the ship’s rail–stared back at Ireland

As the ship picked up speed and headed out to sea

Ireland started to disappear from me

All of a sudden it became such sacred ground

I wanted to scream to the Captain–please turn this ship around

I said to myself you might as well face up to your fate

The next stop for you is the United States

So I wandered around deck sort of aimlessly

All I could hear was the roar of the engines, the sound of the sea

I finally landed in the U.S.

If you think I was thrilled take another guess

No, I am not putting the U.S. down

It just wasn’t my little friendly hometown

I landed in New York but I did not stay

I had to take a train to Philadelphia

Nora met me at Broad Street Station

And that was the end of my destination

But I know God had a hand in my destiny

Because now I have my own fine family

From Ray, Jean, Ann, Richard and Joan

I now have a family like the one I left home

So it’s been worth all the sorrow and grief I’ve been through

To wind up with such a terrific family as you

That’s the end of my story–the end of my poem

I just wanted you to know how it was—the day I left home.

*Originally published in 2023. Updated in 2026.

Stories and Tales

Céad Míle Fáilte, and welcome to your Letter from Ireland on the first week of March 2026. Well now, I think it’s fair to say that most of us here in Ireland are ready to see the back of winter. It has been, by any measure, a remarkable few months of weather, but not in a way that anyone was hoping for. Here in County Cork, the fields are sodden to the point where you’d sink to your ankles taking a short cut across the land. Our local river has burst its banks twice since Christmas, and the farmers I meet wear the particular expression of people who are watching the calendar with a mixture of hope and dread. The question on every farming lip right now is a simple one: when can we get back on the land?

I’m warming my hands on a mug of Barry’s as I write, needs must in weather like this. It struck me that this very question – when can we get back on the land? – is one that your Irish ancestors would have understood in their bones. Because for them, March was not merely a month on the calendar. It was much more than that.

It could be the month that determined everything.

I hope you’ll have a cup of whatever you fancy yourself and join me as we explore what March truly meant in the lives of the Irish families you’re researching.

A Month That Could Make or Break an Irish Family

A few weeks back, I received the following from Tom in Ohio:

“Hi Mike, my great-great-grandfather Patrick Riordan left County Tipperary in the spring of 1848. I always assumed it was the Famine that drove him out, and I’m sure it was, but now I’ve started to wonder – why spring? Why not earlier, or later? Was there something specific about that time of year that pushed families to make the decision to leave? I’d love to understand the rhythm of the year as he would have lived it, Thank you so much, Tom.”

What a well observed question, Tom, and one that gets right to the heart of how the Irish farming year actually worked. The answer, as you suspected, has everything to do with the land, the seed, and the month of March.

The Pivot Point of the Year

For most of Irish history, the rural family’s entire year revolved around a single, brutal calculation: could they grow enough food to survive until the next harvest?

Every season had its role to play, but March was when the year’s fate was truly decided.

This was planting month. The potato, the crop that fed the majority of rural Ireland’s poor by the nineteenth century, went into the ground in March or early April. Miss that window, through illness, waterlogged fields, lack of seed, or through eviction, and you had no meaningful harvest to look forward to come August and September.

But while the arithmetic was merciless, there was a second cruelty built into the season.

March fell squarely within what historians of rural Ireland call the hungry gap – that lean stretch between the exhaustion of the previous year’s stores and the arrival of anything new from the earth. By late winter and early spring, the potato heap was often depleted. Any salted fish was nearly gone, and oatmeal was scarce. And yet here was the moment that demanded the most physical labour of the year: breaking the ground, rebuilding the ridges, preparing the lazy beds, carrying and planting the seed.

Contemporary observers recorded this tension repeatedly. Evidence given to the Devon Commission in the 1840s describes families entering spring “with little remaining but hope and labour.” Parish and Poor Law Union minute books echo the same theme: a hunger rising just as the work intensified.

It is almost impossible to imagine the physical and emotional weight of that combination. Hungry, exhausted, and anxious – but still compelled to work harder than at any other time of the year. Everything your family might eat for the next twelve months depended on what you did in the next few weeks.

When the Cycle Broke

So, understanding this seasonal rhythm helps explain patterns you may have noticed in your own family history.

When potato blight arrived in the autumn of 1845 and devastated subsequent harvests, it wasn’t just a food crisis. It shattered the entire agricultural cycle. The 1845 crop was partially lost; the 1846 harvest failed catastrophically. By the spring planting seasons of 1846 and 1847, many families had no viable seed left to put in the ground.

No seed meant no harvest, and no harvest meant a threat to survival that was felt from labourer all the way up to landlord.

Landlords who had extended credit through the winter called it in. Relief works organised by the British government required labour at precisely the moment smallholders were most needed on their own plots, a bitter irony recorded in countless local accounts.

This helps explain why so many emigration departures clustered in the spring months. March and April represented a moment of clarity. If a family could not plant, there was nothing left to wait for. Passage money, if it could be gathered or borrowed, needed to be spent then – before another hungry summer set in. In your own research, when you see an 1847 or 1848 departure recorded in April or May, you are often looking at the outcome of that seasonal reckoning.

But even in decades before and after the Famine, March shaped your ancestors’ lives profoundly. A cold, wet spring – and Ireland had many – could delay planting by weeks. A warm, dry March could promise abundance. Landlord-tenant tensions often sharpened at this time of year. Rent arrears, ejectment notices, and court records frequently reflect the anxiety of families balancing survival against obligation just as planting began.

When you’re reading Griffith’s Valuation or examining estate papers, you are looking at a snapshot of families who had survived – or not survived – countless such springs. The holdings mapped out on those valuation pages rest, ultimately, on what happened in fields like ours here in Cork every March.

Back to the present…

I stepped outside yesterday morning and the fields across the valley were still showing a grey sheen of water. A neighbouring farmer leaned on his gate and shook his head when I called across.

“T’will be another week at least,” he said, “before I can take the tractor out.”

He could be philosophical about it. He has access to weather forecasts, agricultural advisers, and machinery his grandfather couldn’t have imagined. He knew that he’d be fine in the grander scheme of things.

But standing there in the damp morning air, it was hard not to feel a sharp understanding of what his counterpart nearly 180 years ago might have felt, watching those same fields with so much more at stake, and no certainty at all about what the coming weeks would bring.

This connection, between the land as it is today and the land as your ancestors worked it, is exactly why Irish genealogy is about so much more than names and dates.

So, many thanks to Tom for the question. I’d love to hear from the rest of our readers – does knowing the rhythm of the farming year change how you see your ancestors’ decisions? When you look at a spring emigration date or a tenancy record, does it feel a bit different now?

Slán for now,

Mike.

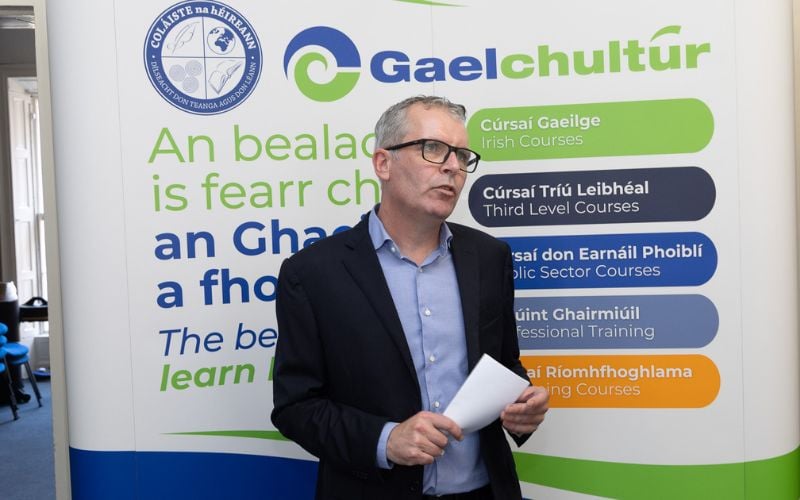

Speak Irish this St. Patrick’s Day:

Free phrasebook launched by Gaelchultúr

The largest provider of Irish language courses, Gaelchultúr, has released a free audio phrasebook to help anyone use authentic Irish phrases confidently at St. Patrick’s Day celebrations worldwide.

With St Patrick’s Day on the horizon, Gaelchultúr, the world’s largest provider of Irish-language courses and resources and Ireland’s Best Language School, is inviting people around the world to celebrate Irish culture in a meaningful way – by using authentic Irish phrases with confidence.

St Patrick’s Day is recognised worldwide as a celebration of Irish identity. Gaelchultúr is encouraging people to go one step further this year by reconnecting with one of the world’s oldest living languages and bringing it into everyday conversations and celebrations.

To mark the occasion, Gaelchultúr has launched a free Irish-Language Phrasebook for St Patrick’s Day. The downloadable resource features carefully selected, authentic Irish expressions, each with English translations and high-quality audio recordings.

Whether you are greeting friends, raising a toast, or sharing a message online, this practical resource makes it easy to use Irish in a way that feels natural, accurate and confident.

“St Patrick’s Day is a powerful global celebration of Irish identity, and the largest celebration of Irish culture worldwide,” explains Clíodhna Ní Chorráin, Gaelchultúr’s Marketing Executive.

“For many, it sparks a curiosity about the Irish language. We want to make Irish feel accessible and welcoming – whether someone wants to learn a few phrases for the day or begin a longer language-learning journey with Gaelchultúr, Ireland’s Best Language School.”

With decades of experience in delivering expert-led Irish-language education, Gaelchultúr has built a vibrant global community of more than 50,000 learners. From Dublin to Sydney, New York to Berlin, people are choosing to reconnect with Irish through Gaelchultúr’s dynamic and engaging programmes.

Driven by a belief that Irish belongs in modern life, Gaelchultúr makes learning the language accessible, practical and fun. Whether someone is rediscovering their heritage, encountering Irish culture for the first time, or simply curious about the language behind the St Patrick’s Day celebrations, Gaelchultúr creates welcoming pathways that turn interest into confidence and connection.

Get your free copy of Gaelchultúr’s audio phrasebook. Click here.

For those wishing to continue their learning beyond St Patrick’s Day, Gaelchultúr offers a comprehensive suite of online Irish-language courses – including live, instructor-led programmes and flexible self-paced options on ranganna.com, providing clear pathways for learners at every stage.

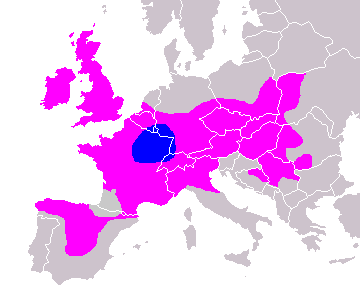

Who Were the Celts?

A Journey Into the Ancient Roots of Irish Identity

If you’ve ever wondered who the Celts were and how Celtic culture and history shaped Irish identity, exploring your Irish Celtic heritage reveals a story far older and richer than most family trees can show.

One of the great joys of discovering you have Irish roots is the moment curiosity turns into connection. You start with a surname, a county, a DNA test, and before you know it, you’re pulled into a much older story.

A story that stretches back long before parish records or passenger lists. A story shaped by a people known as the Celts.

With ancestry and family history tools more accessible than ever, many Irish Americans find themselves asking the same questions: Who exactly were the Celts? And what does Celtic heritage really mean for those of us tracing our family lines back to Ireland?

If you’ve begun researching your Irish ancestry, you’ve likely encountered the term Celtic, sometimes used interchangeably with Irish, sometimes wrapped in mystery, symbolism, and romance.

Understanding who the Celts were helps bring clarity to your family’s past and reveals how deeply their worldview still shapes Irish and Irish American culture today.

What Does “Celtic” Really Mean?

The first surprise for many people is this: the ancient Celts were not exclusively Irish.

While modern culture often links Celtic identity to Ireland and the British Isles, the Celts were once the largest cultural group in ancient Europe.

At their height, Celtic tribes stretched from Ireland and Britain across France, Spain, central Europe, and as far east as modern-day Turkey.

Interestingly, the Celts did not call themselves “Celts.” The name comes from the ancient Greek word Keltoi, a term outsiders used to describe these tribal peoples, often translated as “barbarians,” though that says more about Greek attitudes than Celtic culture.

Rather than a single nation or empire, the Celts were a collection of related tribes, bound together by shared languages, artistic styles, religious beliefs, and social customs. Ireland became one of the places where Celtic culture survived most fully, especially after Roman expansion reshaped much of continental Europe.

The Origins of Celtic Culture

Archaeological evidence suggests that Celtic culture began to emerge around 1200 BC, during the late Bronze Age and early Iron Age. Over centuries, Celtic peoples migrated and settled across vast regions of Europe, adapting to local landscapes while maintaining core traditions.

In Ireland, Celtic society developed without Roman conquest, allowing its language, mythology, and social structures to evolve more independently than elsewhere.

This is one reason Irish culture retains such a strong and recognizable Celtic character today.

Rather than cities or centralized governments, Celtic societies were tribal and kin-based, with strong loyalty to family, land, and ancestry, values that still resonate deeply in Irish and Irish American life.

An Oral Culture: Memory, Story, and the Druids

One of the reasons Celtic history feels elusive is that the Celts left few written records of their own, at least in the early periods. This wasn’t due to ignorance or lack of sophistication. It was a deliberate cultural choice.

Celtic knowledge was preserved through oral tradition: storytelling, poetry, music, law, and ritual passed carefully from one generation to the next. Memory was sacred. Words were powerful.

At the heart of this system were the druids, who served as religious leaders, judges, educators, and historians. They were responsible for preserving laws, genealogies, spiritual beliefs, and collective memory. Training as a druid could take many years, emphasizing learning by heart rather than writing things down.

Later, as Christianity spread through Ireland, monks recorded many of these stories in writing. While they reshaped and reinterpreted them through a Christian lens, much of ancient Celtic mythology survived thanks to this transition.

Beliefs, Art, and the Celtic Worldview

Celtic spirituality was deeply connected to nature and the cycles of the year. Sacred wells, groves, hills, and seasonal festivals marked important moments of transition such as birth, life, death, harvest, and renewal.

Some Celtic practices can feel unsettling to modern readers, including ritual sacrifice in certain regions and periods. But others feel strikingly familiar: reverence for ancestors, belief in the closeness of the spiritual world, and the idea that the veil between worlds can thin at certain times.

Celtic art reflects this worldview. Flowing knotwork, spirals, and interlaced designs symbolize continuity, eternity, and interconnectedness, themes that later became central to Irish Christian art as well.

Ogham: A Distinctly Celtic Form of Writing

One of the most tangible links between the ancient Celts and early Ireland is ogham, a unique writing system that developed in Ireland between the 4th and 6th centuries AD. Ogham was used to write Primitive Irish, one of the earliest recorded Celtic languages, making it a clear expression of Irish Celtic culture rather than a borrowed Roman script.

The ogham alphabet consists of short lines and notches carved along the edge of stone pillars, with most inscriptions recording personal and family names.

These stones often marked land boundaries, burial places, or kinship lines, concerns that lay at the very heart of Celtic society. While ogham may have been influenced by contact with Latin literacy, its form, purpose, and language are deeply rooted in the native Celtic world of Ireland.

Today, ogham stones can still be found standing in the Irish landscape, particularly in the south and west of the country, quietly bearing witness to a society that valued ancestry, memory, and connection to place. They remain powerful reminders that Celtic culture was not only spoken and sung, but also literally carved into the land itself.

How Celtic Culture Lives On Today

Though the ancient Celts are long gone, their influence is everywhere, especially in Ireland and among the Irish diaspora.

Celtic Roots of Halloween

Halloween traces its origins to Samhain, a Celtic festival marking the end of the harvest and the beginning of winter. It was believed that during this time, the boundary between the living and the dead grew thin.

Bonfires, costumes, and symbolic offerings were meant to protect communities and honor ancestors, practices that evolved over time into modern Halloween traditions.

Symbols and Craft

From the Claddagh ring to the Celtic cross, ancient symbols still express values of love, loyalty, faith, and continuity. These designs are more than decorative, they are visual echoes of a Celtic worldview.

Intricate Celtic artwork carved into large stones and boulders, especially the swirling spiral motifs at Newgrange and Knowth, reveals a deep symbolic language rooted in ancient beliefs about cycles, eternity, and the sacred connection between land, life, and the cosmos.

Language

Irish (Gaeilge), Scottish Gaelic, and Welsh all belong to the Celtic language family, descended from the speech of ancient tribes. When you hear Irish spoken today, you’re listening to a living link to the ancient past.

Music

Traditional Irish music, with fiddles, flutes, whistles, pipes, and rhythmic storytelling, reflects the oral culture of the Celts. Music wasn’t entertainment alone. It was memory, history, and identity.

Celtic and Irish: Not the Same, But Inseparable

It’s important to say this clearly: Celtic culture is not identical to Irish culture, but the two are inseparably woven together.

Irish culture grew out of Celtic foundations, shaped later by Christianity, Norse influence, colonization, famine, and emigration. To understand Irish identity fully, especially for those of us in the diaspora, we must understand this deeper Celtic layer beneath the surface.

When you explore your Irish ancestry, you’re not just tracing names and dates. You’re stepping into a story shaped by ancient memory, resilience, and a profound sense of belonging, a story that still lives on in language, music, ritual, and heart.

And perhaps that’s why learning about the Celts feels so personal. Their world may be ancient, but their legacy is alive, in Ireland, in Irish America, and in you.

WATCH: The Irish invented battery-powered trains 85 years before Tesla

An Irish chemist named Dr. James J. Drumm created battery-powered trains, which successfully operated on a Dublin to Bray route from 1932 to 1948.

IrishCentral Staff

Feb 25, 2026

Click below to watch

Irish invented battery-powered trains 85 years before Tesla Ireland Made YouTube

Irish invented battery-powered trains 85 years before Tesla Ireland Made YouTube

Transport historians ‘Ireland Made’ look into the fascinating history of the Irish chemist who created the Drumm Battery Train.

Dr. James J. Drumm was an Irish chemist who did advanced research into the development of powerful traction batteries at University College Dublin (UCD). He completed his college education in 1918 and worked in industry in the UK and Ireland until 1925, when he began his research at UCD.

Sign up to IrishCentral’s newsletter to stay up-to-date with everything Irish!

Drumm was working in the Experimental Physics Laboratory under Professor John J. Nolan, Head of the Department and also an adviser to the Irish Ministry of Industry and Commerce. Drumm was also working on his Ph.D. proposal for a new type of battery chemistry.

In 1929, Drumm applied for a patent on an improved alkaline battery which combined many of the advantages of both alkaline and lead-acid cells. The chief feature of this new chemistry was the high charge and discharge rates achieved.

Compared with contemporaries (notably from the Edison Battery Company), the Drumm battery could charge four times as fast and discharge up to three times as fast, enabling strong acceleration and regenerative braking. The Drumm invention was first made public and attracted widespread interest, not just here in Ireland but across Europe and the US as well.

The Drumm train project was given £27,000, and the Drumm Battery Company was formed. In 1930, a small four-wheeled petrol-driven railcar was modified at the Inchicore rail works. Trial runs showed that the train could reach 80 kph (50 mph) within 50 seconds of the start.

A speed of 88 kph (55 mph), it is stated, was maintained for the greater part of the journey from Dublin to Bray. In February 1932, the Drumm battery train was charged at Inchicore and went on a test run to Portarlington and back — a total distance of 130 kilometers (80 miles) — on a single charge. This was repeated several times, after which the train went into regular service.

Four Drumm Battery train units operated successfully on the Dublin to Bray section of the line with occasional runs to Greystones, some five miles beyond, from 1932 to 1948.

During ‘The Emergency’ years (WWII 1939-1945), coal and petrol shortages affected steam locomotive and road transport. This meant that the Drumm trains had increased use. The war’s impact had a knock-on effect on the company, as it was unable to source raw materials for batteries or secure orders for the Drumm Traction Battery system. Electricity shortages also occurred on the Shannon due to low water levels, affecting the Drumm trains.

By the summer of 1944, the Minister for Industry and Commerce, Sean Lemmas, was non-committal about prolonging the life of the Drumm trains.

A decision was taken to withdraw the trains from service on the 12th of July 1949, when the last Drumm train left Bray. All four railcars were converted at Inchicore into ordinary passenger stock and hauled by steam locomotives. In the mid-1950s, they were withdrawn and replaced by new diesel railcars. These pioneering railcars were scrapped between 1957 and 1964.

Sign up to IrishCentral’s newsletter to stay up-to-date with everything Irish!

Ireland Made tells the stories of Irish transport past and present. You can learn more about their work by following them on Facebook and YouTube.

* Originally published in 2021, updated in Feb 2026.

History and genealogy treasures at the Guinness Storehouse

Guinness Archive has preserved records and artifacts, dating from 1759, including photos, and 20,000 individual personnel records of past employees giving a glimpse into the history of St. James’s Gate and Guinness staff.

Guinness Archive has preserved records and artifacts, dating from 1759, including photos, and 20,000 individual personnel records of past employees giving a glimpse into the history of St. James’s Gate and Guinness staff.

The Guinness Archive, housed by the Guinness Storehouse in Dublin, collects, preserves, and makes accessible records and artifacts from the formation of the company in 1759 to the present day, including 20,000 individual personnel records of past employees.

The foundation document of the Guinness Archive is the 99,000-year lease signed by Arthur Guinness on the St. James’s Gate Brewery in 1759.

The Archive, a treasure chest of Guinness history, is the source of information on all aspects of the history of Guinness, focusing especially on the work and life of the St. James’s Gate Brewery in Dublin. Secure conditions and correct environmental controls ensure the continued preservation of a range of materials, including the advertising, brewing, engineering, social, and personnel records of the company.

Part of the Guinness Archive collection includes over 20,000 individual personnel records of past employees who worked at the Brewery from c. 1880s – early 2000s. Guinness first introduced pensions to all employees in the 1880s and as a result of this initiative, the company began maintaining detailed records on employees which now make up an amazing genealogy resource, unique to corporate archives.

The archive is the direct point of contact for all historical inquiries on the history of Guinness and the archive answers in excess of 5,000 inquiries from all around the world, most notably from consumers in the United States. By far the most requested topic relates to genealogy and such was the demand for genealogy inquiries that a few years ago the archives team undertook an exciting project to digitize a summary of each employee’s work record on the line. This was an exciting innovation and as a result, of this project family, historians can now search the records of their loved ones and ancestors in the genealogy section of www.Guinness-Storehouse.com.

Researchers from all over the world simply type in the name of their relative and can instantly retrieve information such as the employee’s date of birth, date of death, the age at which they joined the brewery, and their occupation. The records also provide information on each department within St. James’s Gate, offering a behind-the-scenes look at what it was like to work in the brewery whether in the brewhouse as an engineer or in the catering department.

For those interested in delving further into their family history, the Guinness Archive is also open by appointment to those who wish to view the original records of their direct relatives. Researchers come from all over the world to trace their ancestors and it is advised that an appointment is made in advance of a visit to the Guinness Archive. Genealogy researchers are accommodated on specific days and times in the Guinness Archive in the Guinness Storehouse.

Due to the financial, medical and often sensitive information in the personnel files, access to personnel files is granted to direct relatives only. The Guinness Archive defines direct relatives as son/daughter, grandson/granddaughter. Information that may be found in the files includes dates of birth, copies of baptismal records, previous employment, character references, the occupation of father, addresses, marital status, children, employment record, family circumstances, medical and financial history.

Very often the records contain a substantial amount of information on an employee as traditionally many employees began their working life at the brewery at the age of 14 and remained in employment until retirement at the age of 65. Guinness earned an excellent reputation through the various welfare initiatives enjoyed by all its staff. As a result, there were few resignations and dismissals were rare.

Employees enjoyed many ‘perks’ at the brewery including free meals, a free pint of Guinness on a daily basis at the ‘Tap’ to employees over the age of 21, free medical care, holiday days, bonuses, and even burial allowances. If an employee died before retirement, his spouse or next of kin received his pension. Depending on the family circumstances the spouse of a deceased employee was often employed as a cleaner or waitress. As a result, the records are a rich genealogy source.

Anecdotally it is said, that older women living in the vicinity of the brewery, whispered to younger women ‘to get yourself a Guinness man as he is worth money alive or dead because of the Guinness pension!’

Eight-hundred Guinness employees also served in World War One and details of where an employee served can also be found in the files. Such was the ethos of the company that an employee received half of their salary while serving during the war and the company established a War Gifts Committee to provide parcels of food and clothing to Guinness employees in the trenches. Following the war, the company commissioned a booklet and memorial plaque entitled ‘The Great War 1914 – 1918, Commemorative Roll,’ which is preserved in the Guinness Archive and lists all the names of employees who fought in the War.

To find out further information on genealogy at the Guinness Archive click here or email [email protected].

* Deirdre McParland has over 15 years of experience in the Archives sector and over seven years working in the Guinness Archive. Originally published in 2016, updated in 2024.

Tommy Mac here….

I know this is a repeat from several years ago,

but I like it!

How the Irish were woken every morning before alarm clocks

Did you ever wonder who the hard-working folks of Ireland managed to get up on time before the invention of the alarm clock? The solution was ingenious… if a little odd.

It wasn’t until the beginning of the 1920s that alarm clocks became readily available, in any kind of reliable form, so how was it that the hard-working people of Ireland and Britain managed to get up in time for work every morning?

The answer is the knocker-upper!

The knocker-up went door to door, literally using a baton or short, heavy stick to knock on their client’s doors or using a long stick, often made of bamboo, would tap on the higher windows of the houses.

At least one knocker-upper, a woman called Mary Smith, used a pea-shooter (see below!) The knocker-up would not leave the house until their client was roused.

In the larger industrial cities, such as London and Manchester, there were large numbers of people employed to carry out this role.

Generally, the job was carried out by older men and women but sometimes police constables would supplement their pay by multi-tasking during their morning patrols.

Alternatively, larger factories and mills would employ their own knocker-up to ensure employees made it to work on time.

Although the clock was certainly the main replacement from the 1920s the BBC reports that until the 1950s and even ’70s the knocker-upper’s work continued in part of Britain.

Next time your alarm clock goes off spare a thought for the knocker-uppers and think of how far technology has come!

*Originally published in Aug 2019. Updated in 2023.

A Lenten pizza penance in 1970s New Jersey

“I can remember the penitential meals that were served on Fridays during Lent in my house. Though I grew up in a Jersey City neighborhood famous for having a killer pizzeria on virtually every corner”

Lent is an adventure in endurance — can a body really go without chocolate and iCarly reruns for 40 days?… Or even really good pizza? iStock

“I gave up social networking for Lent.”

I posted this on my Facebook profile on the morning of Ash Wednesday and within seconds I got the following reply.

“Lent started already, dummy! You’re not into it one day and already you have to find something new to give up.”

It made me swallow hard on my Egg McMuffin, which I realized had meat in it. Right there, my brain on shamrocks kicks into guilt mode.

“Perhaps your kind is more suited for Spy Wednesday,” that little voice inside my head whispered in my ear.

“That’s the day before Holy Thursday, when Judas gave Jesus up. Enjoy that Canadian bacon now, luv, ‘cos I don’t think they serve that down below where yer goin’.”

When it comes to Lent, I just give up. Period.

It says here on the AboutCatholics.com website, “Christian faithful are to do penance through prayer, fasting, abstinence and by exercising works of piety and charity during Lent. All Fridays through the year, and especially during Lent, are penitential days.”

I can remember the penitential meals that were served on Fridays during Lent in my house. Though I grew up in a Jersey City neighborhood famous for having a killer pizzeria on virtually every corner, we did culinary penance with the English muffin pizza. The Irish mother’s recipe went something like this in our house:

*Set oven to broil.

*Split all of the English muffins and place on a baking dish.

*Uncap a large jar of Ragu marinara sauce, placing a dollop in the center of each muffin.

*Release eight slices of Kraft American cheese from the contents of their plastic sleeves.

*Broil until cheese bubbles, about 10 minutes.

Of course, the cheese was more processed than a Britney Spears vocal, which meant it only melted if it struck the surface of the sun. The poor English muffin would be a charcoal disc long before the broiler got to work on the bright orange faux dairy blanket.

It wasn’t until my cousin Rob married an Italian that we got a proper education on the sumptuous delights of snow white shavings of mozzarella cheese melting into the molten, slow-cooked Sunday gravy.

“Faith’n, ye all ate the Ragu that was put in front of yeh and it was good enough at the time,” my Aunt Mary sniffed, finding the prospect of a daughter-in-law outgunning her in the kitchen too hard to swallow.

Can I count dodging my daughters’ pointed questions about what I am giving up for Lent as penance enough? To them, Lent is an adventure in endurance — can a body really go without chocolate and iCarly reruns for 40 days?

Back in my day, we were all given small cardboard piggy banks and encouraged to beg on behalf of the “mission babies” in Africa during the Lenten season. I remember what a thrill it was when we hit $100 in donations as a class- – that’s when we got to name our very own mission babies!

This was back in the 1970s, so I am sure there are plenty of middle-aged Africans running around the jungle angry at their parents for giving them names like Farrah, Fonz, Mork, Mindy, LaVerne and Shirley.

They would probably be a good deal angrier if they knew how many coins I siphoned off the top of the mission baby collection for ice cream and candy. Indeed, I have lots to atone for in my life.

It makes a guy change his McDonald’s order from a Big Mac to a Filet o’ Fish on this particular Friday, just in case this whole Lenten sacrifice thing saves me from the fires of hell. I’d imagine having your soul broiled like an English Muffin pizza would be just a tad painful…

Will to be giving anything up for Lent this year? Let us know below.

(Mike Farragher’s book, This Is Your Brain on Shamrocks, is available now. For more information, click thisisyourbrainonshamrocks.com)

* Originally published in 2011.

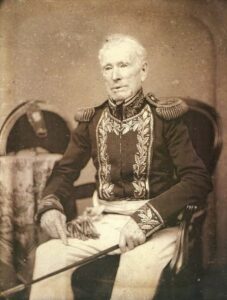

Irish Success Story

The tale of

Admiral William”Guillermo” Brown

News From Ireland

Urgent “risk of imprisonment” and heavy fines warning for Irish in Dubai

Dubai residents and visitors have been issued an urgent warning amid the ongoing conflict in the region.

The UAE has strict cybercrime laws that could cover the posting, reposting or commenting online about the attacks, which could lead to serious fines or even imprisonment.

The warning has been issued by the human rights organisation Detained in Dubai, which campaigns against judicial abuse in the UAE and Gulf region on behalf of expats and tourists.

Dubai is among the cities currently at risk of further missile attacks, as Iran hits back at US bases and Israel following the recent bombardment of Tehran.

The group stated: “The legislation is broad and enforcement can be swift, particularly during periods of heightened security.

“Foreign nationals should exercise extreme caution, as even sharing footage or commentary may result in detention, heavy fines or travel bans.”

Meanwhile, the Irish Embassy in the UAE has been closed on Tuesday due to the ongoing shelter-in-place warning in the region.

The Embassy stated on social media that its location in Abu Dhabi’s public office is shut, though the phone lines will remain open.

Those concerned have been urged to monitor the Embassy’s social media channels for updates and it can be reached at +971 2 495 8200.

Flights in and out of Dubai continue to be cancelled, leaving many Irish citizens stranded in the UAE.

However, the city’s sophisticated air defences have been lauded as doing an “amazing job” in shooting hundreds of missiles fired by Iran.

Debris from the missiles has so far hit major landmarks, including Dubai International Airport, Burj Al Arab Hotel and Jebel Ali Port, as the air defence team works to intercept the strikes.

On Monday, Irish journalist John Hayes spoke to Newstalk Breakfast and said he could still hear the roar of UAE fighter jets patrolling the sky above him.

He told the station about how he believes the city is now overall ‘very safe’, thanks to the ability of the UAE’s military to intercept missiles.

Irish Government to charter flight

for “vulnerable Irish citizens” in UAE

The Irish Government will be chartering a flight for vulnerable citizens seeking to leave the UAE amid the ongoing security situation.

Ireland’s Minister for Foreign Affairs and Defence Helen McEntee has announced that the Irish Government will be chartering a flight for Irish citizens in the UAE.

“I am highly aware of the large numbers of Irish citizens in the UAE as the current conflict continues,” McEntee said in a statment on Tuesday night.

“In this context, I asked our Consular Crisis team today to activate plans for an assisted departure.

“Our team will now take the necessary steps to finalise a first government of Ireland charter flight for Irish citizens to depart the region from Oman Airport in the coming days, providing security and operational considerations permit.

“This first charter flight will be targeted at Irish citizens currently in UAE, particularly those who are non-resident, and who are vulnerable and require assistance most urgently.

“Those citizens requiring most assistance will be contacted directly by my Department in the coming days. I would ask for everyone’s patience as our most vulnerable citizens are contacted in this first phase of our response to this crisis.

“We will continue to offer consular assistance to all citizens in the region. All citizens should register with the appropriate Embassy if they have not already done so and continue to follow our Embassy social media accounts for the latest updates.”

Speaking with RTÉ News on Tuesday night, Minister McEntee acknowledged that “there are different reports as to how long it will take.”

She said she hopes this will be the first of many flights for Irish citizens, and that about 2,000 people have contacted the crisis management office that was set up since Saturday.

McEntee’s statement was published not long after Dublin Airport announced on Tuesday night that airlines had confirmed the cancellation of all 12 flights scheduled for Wednesday to/from Doha, Dubai, and Abu Dhabi.

Dublin Airport cautioned that further disruptions in the coming days are possible.

Disruption to flights between Dublin Airport & airports in the Middle East will continue tomorrow (Wednesday).

Airlines have confirmed the cancellation of all 12 flights scheduled for Wednesday to/from Doha, Dubai & Abu Dhabi. This follows the cancellation of all flights today… pic.twitter.com/01riJnC2Dq

— Dublin Airport (@DublinAirport) March 3, 2026

Advice for Irish citizens in the Gulf Region and Middle East

As of Tuesday night, Ireland’s Department of Foreign Affairs is advising against all travel for Irish citizens to Israel, Iraq, Iran, and Lebanon.

The Department is also advising against all non-essential travel for Irish citizens to Kuwait, Bahrain, the UAE, Qatar, Saudi Arabia, and Jordan.

Irish citizens in the area are being encouraged to register their contact details with the Department.

In an update on Tuesday night, the Irish Embassy in Abu Dhabi, which is accredited to the UAE, Qatar, and Kuwait, said that the situation across the Gulf Region “remains very volatile.”

The airspace over the three countries remained closed as of Tuesday night, and the Irish Embassy said: “Irish citizens should not travel to any airport unless their airlines have confirmed their flights are scheduled to depart.”

The Embassy further said that it was aware that some citizens were considering or had taken the decision to travel by land to neighboring countries.

“Should citizens decide to travel by land, they should be aware that the security situation remains unstable and commercial flight options remain subject to change with limited or no notice,” the Embassy said, adding that it cannot “assess your personal risk en route.”

It continued: “Given the unstable security situation, we are strongly urging citizens not to pursue anything other than essential journeys, to remain vigilant, to monitor developments and media, and to follow advice from local authorities on the ground, including when this is to shelter in place.”

The Embassy encouraged Irish citizens to monitor the Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade’s Travel Advice and the Embassy’s social media channels on X, Instagram, and Facebook.

Also on Tuesday night, the Irish Embassy in Abu Dhabi also posted on social media night about ongoing missile attacks, urging Irish citizens to shelter in place:

— Irish Embassy UAE (@IrelandEmbUAE) March 3, 2026

A new view of old Ireland:

Irish Film Institute publishes collection of historic newsreels

You can stream “Amharc Éireann: A View of Ireland,”

The Irish Film Institute’s collection of historic Irish newsreels, for free.

The Irish Film Institute (IFI) in Dublin, in association with Gael Linn, has launched a new collection of historically significant newsreels, “Amharc Éireann: A View of Ireland.”

This collection of Gael Linn newsreels from the 1950s and 1960s is now available to stream free worldwide on the IFI Archive Player and suite of apps.

Additionally, IFI Digital Platforms has developed a new immersive, interactive map of Ireland, which allows users to explore the collection in depth and find stories relating to villages or counties. Explore over 250 moments – each tied to a village, town, or county – as you browse Ireland geographically.

The interactive map is mirrored on app by Irish tech company Axonista, and the IFI Archive Player app is available to download from Google Play, the App Store, Amazon TV, Android TV, and Roku.

Launching during Seachtain na Gaeilge 2026, the IFI says it is delighted to present 257 films from the Amharc Éireann series, with the support and partnership of Gael Linn and its app provider, Axonista.

What is Gael Linn?

Gael Linn was founded in 1953 with the mission of promoting and revitalising Irish language and culture through a variety of outlets.

The Amharc Éireann newsreel, launched in 1956, was the first regular, indigenous cinema newsreel since the Irish Events newsreel (1917–1920). The newsreel was released initially as a series of short, monthly magazine-style items and later as a weekly issue. A total of 267 editions were released in a five-year period from 1959 and were shown in cinemas across the nation as a curtain raiser to the main feature film. Each episode contained two or three short features of interest to Irish cinema-goers.

The series provides a vivid chronicle of the rapid development of modern Ireland during a particularly progressive period under the stewardship of T.K. Whitaker, Secretary of the Department of Finance, and Taoiseach Seán Lemass.

The series ran until 1964, when the introduction of television and broadcast news ultimately led to a decline in the cinema newsreel as a popular form of information and entertainment. However, the impact of Gael Linn’s Amharc Éireann on Irish cultural identity still resonates today, as these newsreels capture a wealth of historic documentation through an Irish lens.

The key production team comprised producer Colm Ó Laoghaire, cameramen Jim Mulkerns, Vincent Corcoran, and Nick O’Neill, soundman Peter Hunt, scriptwriters Breandán Ó hEithir and Máirtín Ó Cadhain, narrator Pádraic Ó Raghallaigh, and composer Gerard Victory. Other crew members included George Morrisson, Val Ennis, and Morgan O’Sullivan.

“Valuable audio visual record of social history” in Ireland

Speaking upon the launch, IFI Director/CEO Ross Keane said: “The Irish Film Institute is delighted to partner with Gael Linn on this launch of this historically invaluable collection.

“The Amharc Éireann collection is another significant project from the IFI Irish Film Archive that further progresses its vitally important mission of preserving Ireland’s national film heritage.

“We are grateful to Réamonn Ó Ciaráin and all the team at Gael Linn for their collaboration, and to our partners at Axonista for helping bring the collection’s interactive map to life.”

Gael Linn Chief Executive Réamonn Ó Ciaráin added: “Amharc Éireann is a valuable audio visual record of social history portraying Ireland at a time of great social change.

“These short films made a significant contribution to the revitalisation of the Irish language, and they are now set to continue doing so not only in Ireland but across the globe.

“Gael Linn is delighted to be collaborating with IFI on this major initiative which will ensure that Amharc Éireann is accessible now in both Irish and English. ”

Axonista CEO Claire McHugh commented: “Amharc Éireann demonstrates how new technology can unlock archival footage for audiences in entirely new ways.

“By surfacing over 250 stories through an interactive map, we’ve added a powerful layer of place alongside time – enabling viewers to explore Ireland’s history geographically as well as chronologically.

“Axonista’s close, award-winning partnership with IFI since 2017 has been built on exactly this: applying thoughtful technology to deepen cultural discovery and access. ”

In addition to the launch and the materials available free online and via the app, the Irish Film Institute will explore the background to the films’ production and their ongoing cultural value with a screening of MacDara Ó Curraidhín’s documentary “Ireland in the Newsreels” (“Éire na Nuachtscannán”), followed by a panel discussion with Dr. Ciara Chambers of University College Cork, Gael Linn’s Réamonn Ó Ciaráin, Amharc Éireann cameraman Nick O’Neill, journalist Helena Mulkerns, and Áine Gallagher (comedian, Guerrilla Gaeilge Activist). This ticketed event will take place on Monday, March 9, at 6:30 pm.

What’s available to stream on “Amharc Éireann: A View of Ireland”?

The modernisation and economic progress of Irish society in the 1950s and 1960s is documented through a broad array of stories, such as “Thrills for Dubliners: Speedboats on the Liffey,” “Mansion House – Ideal Homes Exhibition,” and a variety of fashion shows.

Industrialisation is charted through newsreels like “Electrification of Connemara” and “Ireland’s First Oil-Fired Power Station.”

However, this modernisation is set alongside the continued importance of the Catholic Church in Ireland, with notable entries including “Annual Blessing of Aer Lingus Fleet” and “Gift of Bull Sent to Pope.”

International celebrities such as Princess Grace of Monaco, John Huston, and Arthur Miller appear, while more everyday events are captured in “Keeping Warm in the Big Freeze” and in films of GAA games, including the 1959 All-Ireland Camogie final between Dublin and Mayo and the 1960 All-Ireland Senior Football semi-final between Kerry and Galway.

A growing interest in international relations is evident in several stories, such as “Irish Forces in the Congo,” while foreign travel was becoming increasingly accessible, as seen in “Dublin-New York: Irish Jet Liner Inaugural Flight” and “Dublin – Malaga: Aer Lingus Start Winter Sunshine Flight.”

A glittering array of nighttime entertainments unspool in the “Nigerian Independence Ball,” at a host of ballroom dancing competitions, and at a student hop where “Art Students Get Twisted.”

The collection paints a complex picture of life across the island at this time, with the nation’s changing economy referenced in stories such as a farmers’ protest march in Limerick and a trade union conference in Buncrana.

Irish cultural life evident in various Fleadhanna Ceoil in Clones, Tuam, and Mullingar, and many historical commemorations which nod to the country’s recent turbulent past. Dramatic hard news stories were regularly captured, such as the 1961 delivery by helicopter of supplies to Inishturk island and the Shannon Air Disaster: 83 Dead, No Survivors.

“Strong uptick” for Ireland’s young adults in religion, study finds

The President of the Irish Catholic Bishops’ Conference said that while the results are not a complete reversal of recent decline, “it is saying something.”

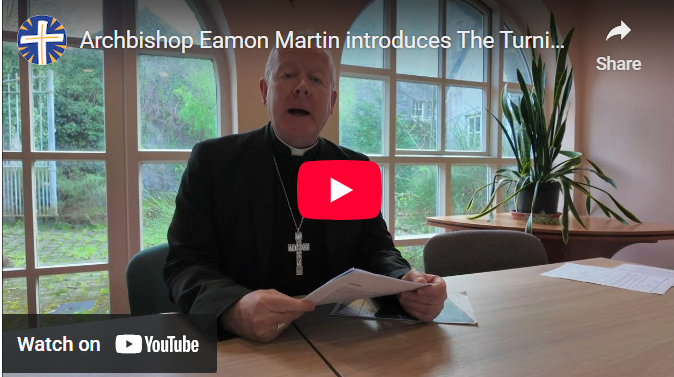

A new report commissioned by the Irish Catholic Bishops’ Conference shows shifting religious trends and signs of renewal among young adults in Ireland.

The report, titled “The Turning Tide? Recent religious trends on the island of Ireland,” provides an analysis of contemporary research into faith practice across the island of Ireland to provide an evidence-based account of recent religious trends.

The report evaluates data from European Social Study (ESS) surveys, the Iona Institute’s two recent surveys (conducted by Amárach Research), and a variety of academic studies, to examine belief, practice, and identity – focusing on Catholicism and other Christian denominations – to highlight regional, generational, and gender trends.

The study, which was discussed at the recent Spring 2026 General Meeting of the Irish Bishops’ Conference, was authored by Stephen Bullivant, Professor of Theology and the Sociology of Religion at Saint Mary’s University, UK, and pharmacist Emily Nelson, who is completing a PhD in Sociology at Queens University Belfast.

Key findings

According to the Irish Bishops’ Conference, among the key findings was that Ireland remains among the more religious countries in Europe based on the measure of religious affiliation, religious service attendance, and frequency of prayer.

Among Western European countries, Ireland is one of very few outliers with a relatively high level of overall religiosity.

Among Catholics specifically, Ireland also ranks towards the higher end of (especially western) European countries on measures of weekly Mass attendance and daily prayer.

While key measures of Irish religiosity have declined significantly since the European Social Survey began in 2002/03, the most recent round – 2023/24 – shows a strong uptick in religious affiliation and religious practice.

This effect is most strongly evident among those aged 16-29 years, across both Catholics and Protestants.

Northern Ireland is both the most religious region of the United Kingdom (by a long way), and the most religious part of the island of Ireland, in terms of both affiliation and religious practice.

Meanwhile, Ireland presents a notable divergence from global patterns: although women in the republic are equally likely to be religious, they continue to play an influential role in transmitting faith, even as they express higher levels of moral dissent and institutional dissatisfaction.

Secularisation is not merely linear, but polarisation is occurring particularly within the Republic of Ireland.

“It is saying something”

Reacting to the findings, Archbishop Eamon Martin, President of the Irish Catholic Bishops’ Conference, said: “The report, very interestingly, does point to some kind of uptick, particularly among young adults, around the ages of 16 to 30.

“The fact that they are taking a new interest in religion and in spirituality – I don’t think we should get ourselves too enthusiastic thinking this is a complete reversal of the very obvious decline in religious practice over the last ten, 20 years.

“However, it is saying something.

“So, ‘The Turning Tide?’ is asking us to reflect on this phenomenon in the light of research and ask ourselves, ‘What does this mean to us as Church, as parishes, as dioceses? How are we responding to this growing body of young people who want to know more about God, about Church, about religion?'”

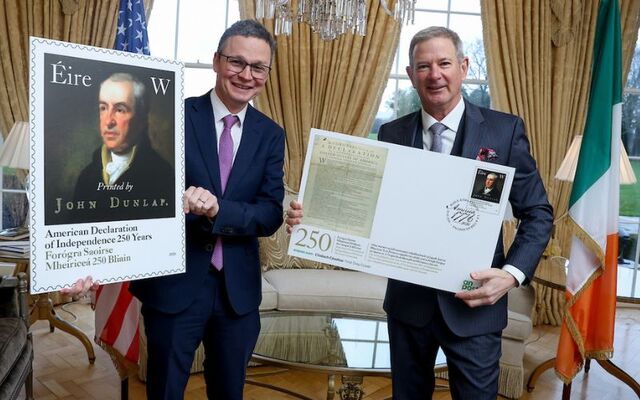

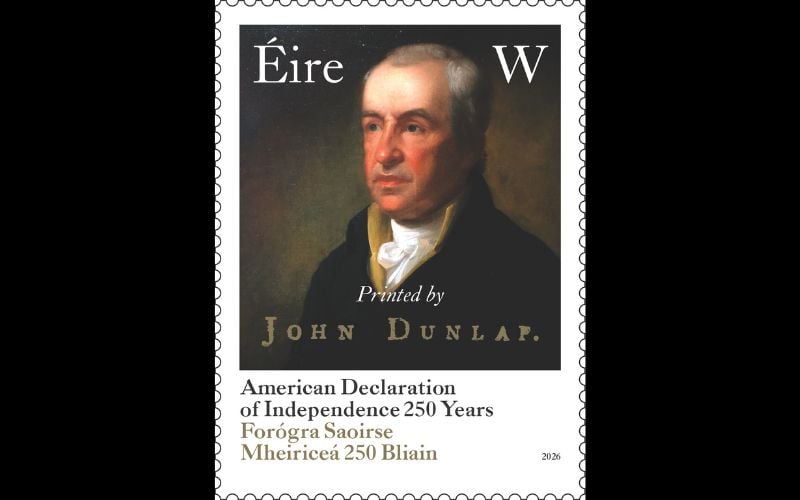

New Irish stamp celebrates Co Tyrone printer

of the American Declaration of Independence

John Dunlap, the Tyrone native who was the printer of the first copies of the Declaration of Independence, is celebrated in a new An Post stamp.

As the US prepares to celebrate the 250th anniversary of the signing of the Declaration of Independence, An Post has issued a new stamp commemorating a unique Irish connection to the document.

The ‘W’ rate stamp for worldwide postage features John Dunlap, who migrated from Strabane in Co Tyrone to America and was the printer of the first copies of the Declaration of Independence.

While Dunlap’s first copies circulated quickly in the American colonies, his prints also reached his home soil – the first newspaper outside of America to publish the Declaration was the Belfast News Letter.

The founding document, which was printed on July 4, 1776, is the basis of political and social change in America. Almost a century later, the powerful themes of the American Declaration were clearly echoed in the 1916 Proclamation of Irish Independence.

Designed by Dublin design agency Detail, the classic stamp design features Dunlap’s portrait by artist Rembrandt Peale. His signature is incorporated into the design, representing his role as printer of the Declaration.

The W-rated stamp and a limited edition First Day Cover are available for purchase at selected post offices in Ireland or at anpost.com/shop.

“John Dunlap’s story reflects the profound influence of the Irish diaspora in shaping pivotal moments in global history.

“The ideals expressed in the Declaration of Independence – liberty, equality, and democratic self-determination – resonated far beyond America’s shores and would later find powerful expression in Ireland’s own struggle for independence.

“It is fitting that An Post marks this 250th anniversary by honouring an Irishman whose work helped give voice to one of the most important documents in modern history.”

Marking 250 years of the American Declaration of Independence.

Minister Patrick O’Donovan and U.S. Ambassador Ed Walsh unveil a new “W” rate stamp honouring Co. Tyrone native John Dunlap, printer of the first Declaration copies.https://t.co/8iihQlmsA2 pic.twitter.com/RAeH5S9QDU

— An Post (@Postvox) February 26, 2026

US Ambassador to Ireland Ed Walsh added: “As the United States marks 250 years of independence, this commemorative stamp is a meaningful tribute to Ireland’s role in America’s founding story.

“John Dunlap, born in County Tyrone, printed the first copies of the Declaration of Independence in Philadelphia.

“Irish Americans fought for our independence, helped design and build the White House, served with distinction in our armed forces, and contributed to American public life and innovation.

“As we mark this milestone, we recognise the strong and lasting friendship between our nations.”

St. Patrick must have missed one!…Tommy Mac

Nine-year-old boy finds one of the world’s deadliest snakes in Offaly

Fionn Kilmurray found a saw-scaled viper on Sunday. The snake is responsible for more human fatalities than any other.

A nine-year-old boy in County Offaly had a Sunday to remember when he came across one of the most dangerous snakes in the world in his own back garden.

Fionn Kilmurray found a saw-scaled viper, a highly dangerous snake responsible for more human deaths than any other, lying in the garden on Sunday afternoon.

The snake is believed to have made its way to Ireland on a consignment of stone shipped from India. This is the first time that the snake has been found in Ireland.

He alerted his mother Aoife to the shocking discovery and she told RTÉ News that he was acting “cool as a cucumber”.

Read more: Did St. Patrick really banish all the snakes from Ireland?

Aoife Kilmurray said that the family was unaware of how dangerous the snake was and remained calm as a result. She said that she called the National Reptile Zoo and said that she was glad she didn’t know how dangerous the snake was until an expert with the zoo had traveled to their home in Rhode, Offaly.

She sent photographs of the snake to the National Reptile Zoo while she waited for the expert to arrive and James Hennessy, the zoo’s director, said that staff at the zoo knew just how dangerous the snake was by simply looking at the photos.

The National Reptile Zoo advised Aoife Kilmurray to put a box over the snake until help arrived.

The snake was taken to the National Reptile Zoo in Kilkenny and will likely be transported to a research center in the United Kingdom for anti-venom research.

James Hennessy, meanwhile, said that the incident highlighted the need for stricter monitoring of cargo contents to avoid similar cases in the future.

For nine-year-old Fionn Kilmurray, the incident was “just brilliant” and he was itching to go to school on Monday to show his friends pictures of the snake.

Read more: The real reason why there aren’t any snakes in Ireland

Jokes

Dad Jokes

Why should you never trust stairs?

They’re always up to something.

Funnies From My Wife

Funny Headlines

Times when you might be excused for using foul language

What’s that in the water with her????

Funny Statue Photos

That’s got to hurt

Funny Signs

Many news items, stories, recipes, jokes, and poems are taken from these sites

with their generous permission.

Please support them by clicking on the links below

and sign up for their free newsletter.

Welcome to

Tír na mBláth

Tír na mBláth is one of hundreds of branches throughout the world of Comhaltas Ceoltóirí Éireann (CCÉ) pronounced “kol-tus kyol-tori air-in“, the largest group involved in the preservation of Irish music, dance and song.

Our board and membership is made up of Irish, Irish descendants, and all those who support, celebrate and take pride in the preservation of Irish culture.

We also aim to promote good will and citizenship.

Interested in belonging to Tír na mBláth? Feel free to download our membership form

Facebook page is at Tír na mBláth

Our meetings and several events are held at Tim Finnegan’s Irish Pub in Delray Beach Florida.

Well, that's it for this week.

Number of visitors to this website since Sept 2022